Santa Claus is Coming to Town

#santa #christmas

Every mother’s child on Christmas eve is going to spy to see if the reindeer really knows how to fly. So says the popular Christmas song sung in America. The big fat man in a big red suit comes through the chimney and brings lots of goodies for the kids. For him hangs the socks over the hearth; cookies and a glass of milk await for the jolly man. All through the year he makes toys in his workshop in the North Pole with the help of the elves. Then on Christmas eve he makes a round of the whole world, bringing toys to the sleeping children.

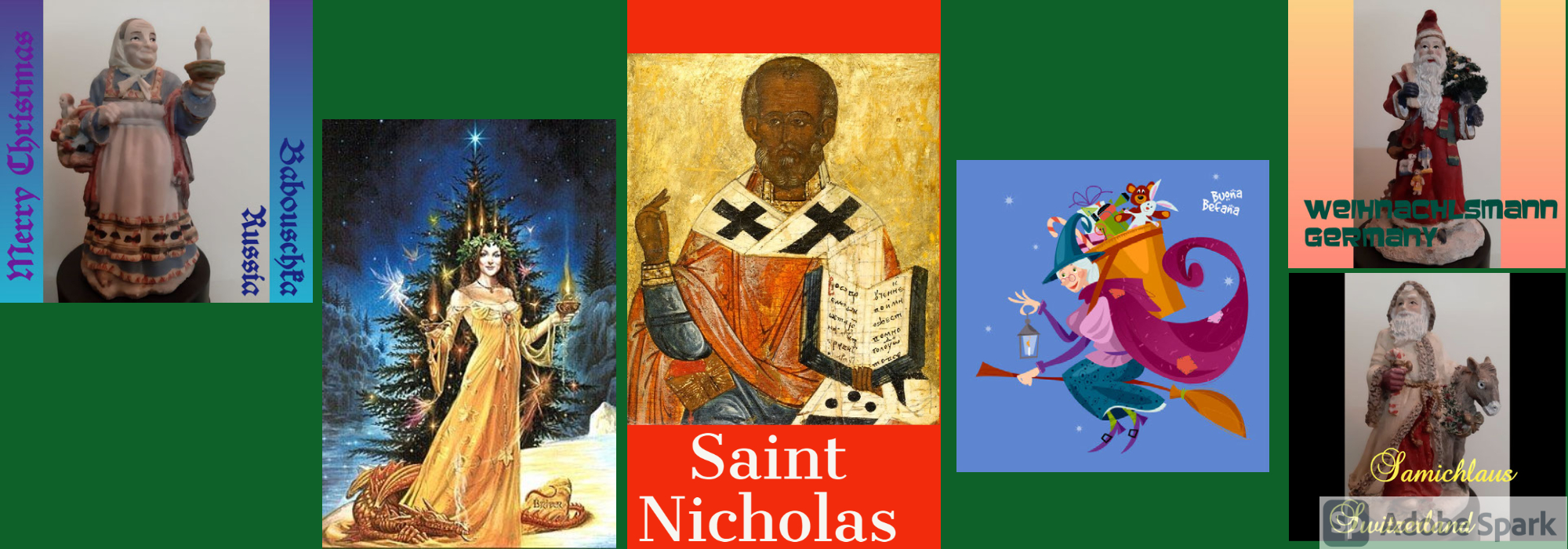

If you think this is the one and only Santa Claus, known all over the world, you cannot be more wrong! This particular Santa is only an American Santa. He was not much familiar in the other Christian countries even in the early twentieth century. That is not to say that the tradition of Santa Claus is merely a New World affair. It is not. In fact, strange that it may sound, the earliest legend of Santa Claus originated in the extreme eastern part of the Christian Empire, in Asia Minor, which is today’s Turkey.

We often forget that Christianity originated in Asia and the legends and folk tales are less likely to be all-European.

The 4th century Bishop of Myra, Saint Nicholas, was tall and lean. He was much venerated through the Middle Ages and became a Patron Saint in Russia and Greece, the two countries where Orthodox Christianity held sway for long. December 6 was his feast day and a church holiday throughout Europe. For some reason, after Reformation, he fell into disrepute and his feast day was merged with Jesus Christ’s official birthday on December 25!

Even though Saint Nicholas lost his veneration, his repute as a gift giver survived. Like every folk legend, the legend of Santa Claus is full of strange tidings. In Holland, the only Protestant country where Saint Nicholas survived for many centuries, the Dutch children put their shoes, and not oversized stockings, in front of the fireplace and some food for Sinterklaas’ horse. He has a Moorish assistant, named Black Peter, and they come from Spain in a ship. Then Sinterklaas mounts on a white horse, wearing a white robe and red cassock, gallops from roof to roof, but Black Peter follows on foot. Since Sinterklaas does not want to soil his lovely dress, he never squeezes through the chimney, the Moor has to do that. He comes down the chimney and leaves the gifts in the shoes, but Sinterklaas only drops the candies into the shoes from high above!

Dark Peter was known to carry a chimney sweep’s broom and spank naughty children with it. It is also rumored that he puts the most spoilt ones in his sack and whisk them off to Spain.

During the Middle Ages Black Peter happened to be a common nick name for the Devil. It is said that before his birthday Saint Nicholas kidnaps the Devil and makes him his assistant in doing good to the world. The history behind Black Peter’s appearance in Dutch legend as a Moor may have originated in the sixteenth century when they suffered under the Spanish rule. Was it because the Medieval Europeans portrayed the Devil with a dark skin, the north African ethnic group, who reigned over a part of Southern Spain for many centuries, became Dark Peter?

Next door to Holland, in Germany, the Santa like character goes by many different names. Der Weihnachtsmann, or The Man of the Watch Night is a bearded old man, trudging through the snow with a small Christmas Tree over his shoulder.

When Christianity took firm roots in Europe, it tried to sweep all paganism away, but ended with assimilating many into its customs. Berchta was one pagan goddess of Germany and Northern Europe. She used to visit in the winter nights long before Christianity, and now makes her appearances during the Twelve Nights of Christmas. She blesses the home and the hearth, makes the land fertile when she flies over them, brings gifts for well-behaved children and rocks the baby’s cradle when no one is looking. Each household is supposed to prepare special food, consume it and leave the remaining for her. If not, Lo and Behold, Berchta will cut open the stomachs of the inhabitants and remove the content.

There are two other female characters, Baboushka in Russia and Befana in Italy, who are also the bringers of gifts for children. Baboushka or the Grandmother, lived all by herself in a house by the side of a road. Her days were filled with cleaning, cooking, scrubbing, spinning, sweeping and dusting. One strange night three strangers knocked on her door and asked her the way to Bethlehem where a New King is born. They had gifts for the new born and asked her to join them on their journey. But Baboushka refused as she had not finished her daily chores. But, after a while, she began wondering about this baby who would one day be a King. Baboushka collected a few trinkets from among her poor possessions and started in the cold night but she never found the Three Magi nor the Baby Jesus. Each year on the Twelfth Night she searched all over Russia for the Christ Child. She enters every home and even if she could not find Him, she leaves small trinkets for the good and well-mannered children.

The legend of La Befana in Italy is exactly similar. She also looks for the Child and bestows sweets and gifts for the children.

In Russia poor Baboushka was shunned during the Communist Regime, as her story referred to religious beliefs directly. A Grandfather Frost was brought in officially in her place as a secular gift-giver.

Samichlaus and his assistant Schmutzli visit the Swiss children during day time with a donkey in tow. On December 6 they emerge from their cottage in the woods and visit every home, school or other places where children are found. They tell stories to the children and the children in turn recite poems. Schmutzli gives each child a gingerbread cookie. Then emptying his sack he gives the children piles of walnuts, peanuts, chocolates and other goodies.

Strange, isn’t it, how ancient Roman and Pagan customs and folklores continue to stay under the veneer of Christianity? Gift giving is probably the most attractive part of Christmas celebration, at least for the children. The consumerist economy builds on it, but the custom of gift exchanges around mid-winter has been around since the Roman time. As early as the sixteenth century German children received gifts comprised of eatables, such as nuts, cookies, sugarplums, apples, and small coins, religious books or writing material. Often a small stick also was packed inside as a reminder that chastisement is only waiting round the corner!

Comments

Reply here

Santa Claus is coming to town

Excellent write up with so many informations.

Mamata Dasgupta

12-12-2020 06:21:14